Via: Telegraph

The capital well is running dry and some economies will wither

The world is running out of capital. We cannot take it for granted that the global bond markets will prove deep enough to fund the $6 trillion or so needed for the Obama fiscal package, US-European bank bail-outs, and ballooning deficits almost everywhere.

By Ambrose Evans-Pritchard

Last Updated: 8:49AM BST 26 Apr 2009

Unless this capital is forthcoming, a clutch of countries will prove unable to roll over their debts at a bearable cost. Those that cannot print money to tide them through, either because they no longer have a national currency (Ireland, Club Med), or because they borrowed abroad (East Europe), run the biggest risk of default.

Traders already whisper that some governments are buying their own debt through proxies at bond auctions to keep up illusions – not to be confused with transparent buying by central banks under quantitative easing. This cannot continue for long.

Commerzbank said every European bond auction is turning into an "event risk". Britain too finds itself some way down the AAA pecking order as it tries to sell £220bn of Gilts this year to irascible investors, astonished by 5pc deficits into the middle of the next decade.

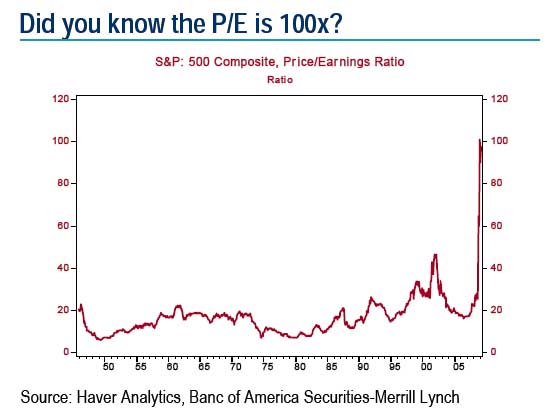

US hedge fund Hayman Advisers is betting on the biggest wave of state bankruptcies and restructurings since 1934. The worst profiles are almost all in Europe – the epicentre of leverage, and denial. As the IMF said last week, Europe's banks have written down 17pc of their losses – American banks have swallowed half.

"We have spent a good part of six months combing through the world's sovereign balance sheets to understand how much leverage we are dealing with. The results are shocking," said Hayman's Kyle Bass.

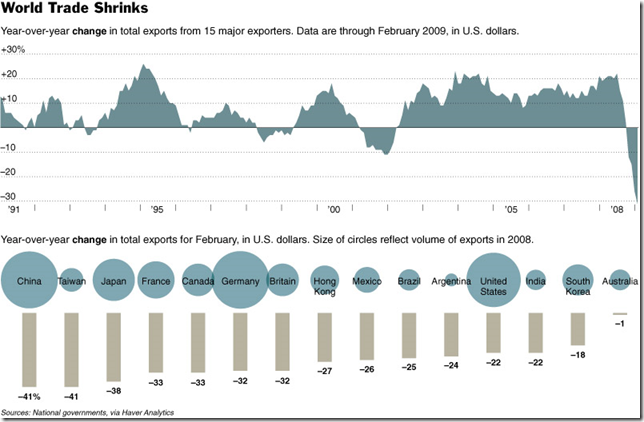

It looked easy for Western governments during the credit bubble, when China, Russia, emerging Asia, and petro-powers were accumulating $1.3 trillion a year in reserves, recycling this wealth back into US Treasuries and agency debt, or European bonds.

The tap has been turned off. These countries have become net sellers. Central bank holdings have fallen by $248bn to $6.7 trillion over the last six months. The oil crash has forced both Russia and Venezuela to slash reserves by a third. China let slip last week that it would use more of its $40bn monthly surplus to shore up growth at home and invest in harder assets – perhaps mining companies.

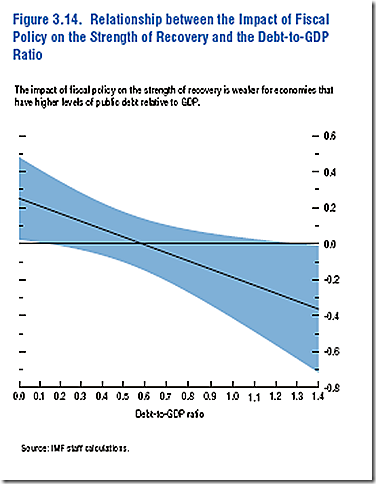

The National Institute for Economic and Social Research (NIESR) said last week that since UK debt topped 200pc of GDP after the Second World War, we can comfortably manage the debt-load in this debacle (80pc to 100pc). Variants of this argument are often made for the rest of the OECD club.

But our world is nothing like the late 1940s, when large families were rearing the workforce that would master the debt. Today we face demographic retreat. West and East are both tipping into old-aged atrophy (though the US is in best shape, nota bene).

Japan's $1.5 trillion state pension fund – the world's biggest – dropped a bombshell this month. It will start selling holdings of Japanese state bonds this year to cover a $40bn shortfall on its books. So how is the Ministry of Finance going to fund a sovereign debt expected to reach 200pc of GDP by 2010 – also the world's biggest – even assuming that Japan's industry recovers from its 38pc crash?

Japan is the first country to face a shrinking workforce in absolute terms, crossing the dreaded line in 2005. Its army of pensioners is dipping into the collective coffers. Japan's savings rate has fallen from 14pc of GDP to 2pc since 1990. Such a fate looms for Germany, Italy, Korea, Eastern Europe, and eventually China as well.

So where is the $6 trillion going to come from this year, and beyond? For now we must fall back on the Fed, the Bank of England, and fellow central banks, relying on QE (printing money) to pay for our schools, roads, and administration. It is necessary, alas, to stave off debt deflation. But it is also a slippery slope, as Fed hawks keep reminding their chairman Ben Bernanke.

Threadneedle Street may soon have to double its dose to £150bn, increasing the Gilt load that must eventually be fed back onto the market. The longer this goes on, the bigger the headache later. The Fed is in much the same bind. One wonders if Mr Bernanke regrets saying so blithely that Washington can create unlimited dollars "at essentially no cost".

Hayman Advisers says the default threat lies in the cocktail of spiralling public debt and the liabilities of banks – like RBS, Fortis, or Hypo Real – that are landing on sovereign ledger books.

"The crux of the problem is not sub-prime, or Alt-A mortgage loans, or this or that bank. Governments around the world allowed their banking systems to grow unchecked, in some cases growing into an untenable liability for the host country," said Mr Bass.

A disturbing number of states look like Iceland once you dig into the entrails, and most are in Europe where liabilities average 4.2 times GDP, compared with 2pc for the US. "There could be a cluster of defaults over the next three years, possibly sooner," he said.

Research by former IMF chief economist Ken Rogoff and professor Carmen Reinhart found that spasms of default occur every couple of generations, each time shattering the illusions of bondholders. Half the world succumbed in the 1830s and again in the 1930s.

The G20 deal to triple the IMF's fire-fighting fund to $750bn buys time for the likes of Ukraine and Argentina. But the deeper malaise is that so many of the IMF's backers are themselves exhausting their credit lines and cultural reserves.

Great bankruptcies change the world. Spain's defaults under Philip II ruined the Catholic banking dynasties of Italy and south Germany, shifting the locus of financial power to Amsterdam. Anglo-Dutch forces were able to halt the Counter-Reformation, free northern Europe from absolutism, and break into North America.

Who knows what revolution may come from this crisis if it ever reaches defaults. My hunch is that it would expose Europe's deep fatigue – brutally so – reducing the Old World to a backwater. Whether US hegemony remains intact is an open question. I would bet on US-China condominium for a quarter century, or just G2 for short.