The Benign Brodwicz program for the United Snakes of America is and always has been this:

Pay for the dole by raising marginal tax rates on our super-greedy, klepto-plutocracy, aka the American ruling class.

Die young, live fast: The evolution of an underclass

Editorial: Why biology should inform social policy

FROM feckless fathers and teenaged mothers to so-called feral kids, the media seems to take a voyeuristic pleasure in documenting the lives of the "underclass". Whether they are inclined to condemn or sympathise, commentators regularly ask how society got to be this way. There is seldom agreement, but one explanation you are unlikely to hear is that this kind of "delinquent" behaviour is a sensible response to the circumstances of a life constrained by poverty. Yet that is exactly what some evolutionary biologists are now proposing.

There is no reason to view the poor as stupid or in any way different from anyone else, says Daniel Nettle of the University of Newcastle in the UK. All of us are simply human beings, making the best of the hand life has dealt us. If we understand this, it won't just change the way we view the lives of the poorest in society, it will also show how misguided many current efforts to tackle society's problems are - and it will suggest better solutions.

Evolutionary theory predicts that if you are a mammal growing up in a harsh, unpredictable environment where you are susceptible to disease and might die young, then you should follow a "fast" reproductive strategy - grow up quickly, and have offspring early and close together so you can ensure leaving some viable progeny before you become ill or die. For a range of animal species there is evidence that this does happen. Now research suggests that humans are no exception.

Certainly the theory holds up in comparisons between people in rich and poor countries. Bobbi Low and her colleagues at the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor compared information from nations across the world to see if the age at which women have children changes according to their life expectancy (Cross-Cultural Research, vol 42, p 201). "We found that the human data fit the general mammalian pattern," says Low. "The shorter life expectancy was, the earlier women had their first child."

But can the same biological principles explain the difference in behaviour between rich and poor within a developed, post-industrialised country? Nettle, for one, believes it can. In a study of over 8000 families, he found that in the most deprived parts of England people can barely expect 50 years of healthy life, nearly two decades less than in affluent areas. And sure enough, women from poor neighbourhoods are likely to have their babies at an early age and in quick succession. They have smaller babies and they breastfeed less, both of which make it easier to get pregnant again sooner (Behavioral Ecology, DOI: 10.1093/beheco/arp202).

In the most deprived parts of England, people can barely expect 50 years of healthy life - two decades less than in affluent areas

"If you've only got two-thirds as much time in your life as someone in a different neighbourhood, then all of your decisions about when to start having babies, when to become a grandparent and so on have to be foreshortened by a third," says Nettle. "So it shouldn't really surprise us that women in the poorest areas are having their babies at around 20 compared to 30 in the richest ones. That's exactly what you would expect."

Consciously or subconsciously, women do seem to take their future prospects into account when deciding when to start having children. At a meeting last year, Sarah Johns at the University of Kent in Canterbury, UK, reported that in her study of young women from a range of socioeconomic backgrounds in Gloucestershire, UK, those who perceived their environment as risky or dangerous, and those that thought they might die at a relatively young age, were more likely to become mothers while they were in their teens. "If your dad died of a heart attack at 45, your 40-year-old mum has got chronic diabetes and you've had one boyfriend who has been stabbed, you know you've got to get on with it," she says.

It's the same story in the US. The latest figures, from 2005, reveal that teenage motherhood accounts for 34 per cent of first births among African Americans - who are more likely to live in deprived areas - and 19 per cent among whites. Arline Geronimus of the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor, who has studied health inequalities and reproductive patterns, points out that healthy life expectancy is short for African Americans and women depend on extended family networks for support. This means it is in their interests to have children while they still have relatives in good physical shape to help out.

The shockingly rapid deterioration in health experienced by women in poor black neighbourhoods also directly affects mothers. Even women in their 20s have an increased risk of conditions such as hypertension that would reduce the chance of a healthy pregnancy and birth. In research carried out in the late 1990s, Geronimus and her colleagues found that in Harlem, a poor neighbourhood in New York City, the infant mortality rate for babies born to mothers in their 20s was twice that of the babies of teenage mums (Political Science Quarterly, vol 112, p 405). Geronimus thinks the situation may be even worse now, given that the rate of health deterioration in black women has increased in the past decade.

It is not simply a case of teenage girls from deprived backgrounds accidentally becoming pregnant. Evidence from many sources suggests that teen pregnancy rates are similar in poor and affluent communities. However, motherhood is a choice, as both Geronimus and Johns are keen to point out. Teenage girls from affluent backgrounds are more likely to have abortions than their less-privileged peers. In terms of reproduction, the more affluent girls are best off concentrating on their own career and development so that they can invest more in the children they have at a later stage. "It seems that girls are assessing their life chances on a number of fronts and making conscious decisions about reproduction," says Johns.

Another important issue is whether or not a girl's father is around when she is growing up. Developmental psychologist Bruce Ellis, of the University of Arizona in Tucson, has studied extensively the effects of girls' relationships with their fathers. His research shows that the less involved a father is with his daughter from an early age, and the less warm the relationship, the earlier she starts having sex and, potentially, babies (New Scientist, 14 February 2007, p 38).

Fathers in deprived neighbourhoods are more likely to be absent, which could be because they are following "fast" strategies of their own. These include risky activities designed to increase their wealth, prestige and dominance, allowing them to compete more successfully with other men for sexual opportunities. These needn't necessarily be antisocial, but often they are. "I'm thinking about crime here, I'm thinking about gambling," says Nettle, and other risky or violent behaviours that we know are typical of men in rough environments. A fast strategy also means a father is less likely to stick with one woman for the long term, reducing his involvement with his children.

Paternal benefits

That is unfortunate, since a father's involvement not only delays his daughter's reproduction but also has a big impact generally on the life chances of his children. In a study of 17,000 people in the UK born in a single week in March 1958, Nettle found that where father involvement was greater, children had higher IQ scores at age 11 and increased upward social mobility through adulthood (Evolution and Human Behavior, vol 29, p 416).

Lower investment in children, whether it be through the absence of dad, less breastfeeding from mum, or less parental attention generally because there are more children in the family, comes at a high cost to the children themselves. For one thing, Nettle's large-scale study of families in England found that babies born in the poorest areas have slower cognitive development, which compromises their education and prospects later in life.

To all this you might ask the question, aren't poor people bringing their problems on themselves? If only they would wait a while before starting to have babies they might be able to invest more in each one, providing a better diet and healthier lifestyle. It is not so simple. "Children of low income, low education families don't do well regardless of what their parents' age is," says Johns. What's more, youngsters who delay parenthood may actually be worse off. "In a US study looking at pairs of low-income sisters, the ones that became mothers in their teens quite often did better [in terms of employment and earnings] because they had something to focus their energy into and create a better life for."

Nettle agrees: "Overwhelmingly the poverty into which a baby is born is going to be a big influence, whatever the age of the mother. It may be that there's not much pay-off for waiting and doing other, more middle-class behaviours that public health people want to encourage the poor to do."

People in deprived areas face two kinds of hazard, Nettle says. First, there are constraints on what they are able to do to mitigate their situation. Diet is a prime example: "It's much more expensive to get 2000 calories a day from fresh fruit and vegetables compared with eating junk food," Nettle says. Then the environment is often physically more dangerous and unhealthy. "People are doing more dangerous jobs. There is probably more air pollution, more car accidents, a higher crime rate, poorer housing - things you cannot really do much about, which trigger a downward spiral of faster living and less attention to health."

Once you are in a situation where the expected healthy lifetime is short whatever you do, then there is less incentive to look after yourself. Investing a lot in your health in a bad environment is like spending a fortune on maintaining a car in a place where most cars get stolen anyway, says Nettle. It makes more sense to live in the moment and put your energies into reproduction now.

Evolutionary theory can explain these behavioural responses to poverty, but it doesn't make them desirable. So what is the answer? What can be done to help people escape from the slippery slope of poor health, poor education and deprivation?

Governments are very good at being concerned about rates of teenage pregnancy and violence among young men, but Nettle argues that no amount of money poured into sex education and parenting classes will change the situation if young people don't see a decent future for themselves. To change behaviour we have to change the environment, which means that actually reducing poverty in the most deprived areas is likely to do a much better job than education schemes or handing out morning-after pills.

No amount of money poured into sex education and parenting classes will change the situation if young people don't see a decent future for themselves

Perhaps the most compelling evidence for this comes from real-life situations. In the mid-1990s, the residents of one poor, mainly Native American district in North Carolina each received a windfall in the form of royalties from a casino that had been built on their land. After the windfall, the researchers recorded a significant reduction in conduct disorder - the psychologist's term for antisocial behaviour - among the poorest children (The Journal of the American Medical Association, vol 290, p 2023).

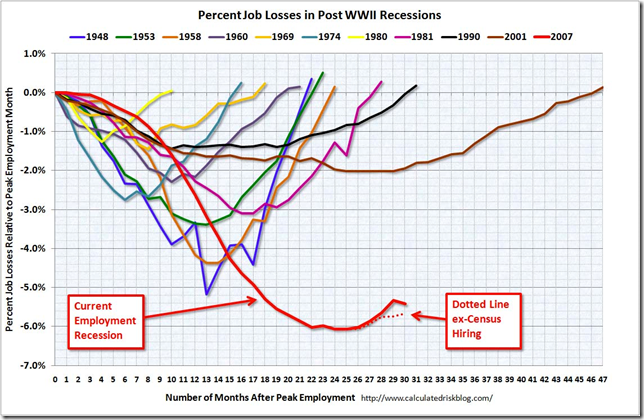

On a larger scale, during the 1990s there was a dramatic decline in teenage birth rates in the US, especially among African Americans. In 1993, 6.4 per cent of black girls aged between 15 and 17 became first-time mothers but by 2000 this had dropped to 4.5 per cent (Social Science and Medicine, vol 63, p 1531). Geronimus puts this down in part to the strong economic expansion and increase in employment rates during this time, which offered young black women job opportunities they were unlikely to have had before. Teen births among African Americans are now rising again, predictably, given the recent economic nosedive.

It's all relative

Still, reducing poverty alone probably isn't the answer. In their book The Spirit Level (Allen Lane, 2009), epidemiologists Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett, of the universities of Nottingham and York, UK, respectively, emphasise the degree of income inequality in a society rather than poverty per se as being a major factor in issues such as death and disease rates, teenage motherhood and levels of violence. They show that nations such as the US and UK, which have the greatest inequality in income levels of all developed nations, also have the lowest life expectancy among those nations, the highest levels of teenage motherhood (see diagrams) and a range of social problems.

The effects are felt right across society, not just among poor people. "Inequality seems to change the quality of social relations in society," says Wilkinson, "and people become more influenced by status competition." Anxiety about status leads to high levels of stress, which in turn leads to health problems, he says. In unequal societies trust drops away, community life weakens and society becomes more punitive because of fear up and down the social hierarchy.

"Really dealing with economic inequalities is difficult because it involves unpopular things like raising tax," says Nettle. "So rather than fighting the fire, people have been trying to disperse the smoke." Politically it is much easier to pump money into education programmes even if the evidence suggests that these are, on the whole, pretty ineffective at reducing the effects of poverty.

There are two quite different ways that societies can be made more equal, Wilkinson says. Some countries, like Sweden, do it by redistribution, with high taxes and welfare benefits. In others, earnings are less unequal in the first place. Japan is one such country, and it has one of the highest average life expectancies and lowest levels of social problems among developed nations. Other important factors, says Wilkinson, are strong unions and economic democracy.

The bottom line, if young people are to avoid being channelled into a fast reproductive strategy with the disadvantages that this entails, is that they should have the chance to develop a longer view - through better availability of jobs and health support. They need reasons to believe they have a stake in the future.

Mairi Macleod is a journalist based in Edinburgh, UK